PA Media

PA MediaThe UK is about to stop producing any electricity from burning coal – ending its 142-year reliance on the fossil fuel.

The country’s last coal power station, at Ratcliffe-on-Soar, finishes operations on Monday after running since 1967.

This marks a major milestone in the country’s ambitions to reduce its contribution to climate change. Coal is the dirtiest fossil fuel producing the most greenhouse gases when burnt.

Minister for Energy Michael Shanks said: “We owe generations a debt of gratitude as a country.”

The UK was the birthplace of coal power, and from tomorrow it becomes the first major economy to give it up.

“It’s a really remarkable day, because Britain, after all, built her whole strength on coal, that is the industrial revolution,” said Lord Deben – the longest serving environment secretary.

The first coal-fired power station in the world, the Holborn Viaduct power station, was built in 1882 in London by the inventor Thomas Edison – bringing light to the streets of the capital.

Oxford Science Archive/Getty Images

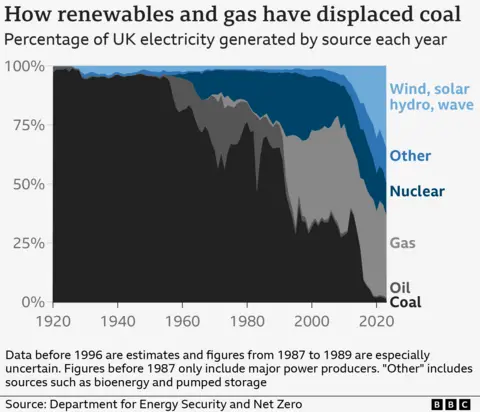

Oxford Science Archive/Getty ImagesFrom that point through the first half of the twentieth century, coal provided pretty much all of the UK’s electricity, powering homes and businesses.

In the early 1990s, coal began to be forced out of the electricity mix by gas, but coal still remained a crucial component of the UK grid for the next two decades.

In 2012, it still generated 39% of the UK’s power.

The growth of renewables

But the science around climate change was growing – it was clear that the world’s greenhouse gas emissions needed to be reduced and as the dirtiest fossil fuel, coal was a major target.

In 2008, the UK established its first legally binding climate targets and in 2015 the then-energy and climate change secretary, Amber Rudd, told the world the UK would be ending its use of coal power within the next decade.

Dave Jones, director of global insights at Ember, an independent energy think tank, said this really helped to “set in motion” the end of coal by providing a clear direction of travel for the industry.

But it also showed leadership and set a benchmark for other countries to follow, according to Lord Deben.

“I think it’s made a big difference, because you need someone to point to and say, ‘There, they’ve done it. Why can’t we do it?'”, he said.

In 2010, renewables generated just 7% of the UK’s power. By the first half of 2024, this had grown to more than 50% – a new record.

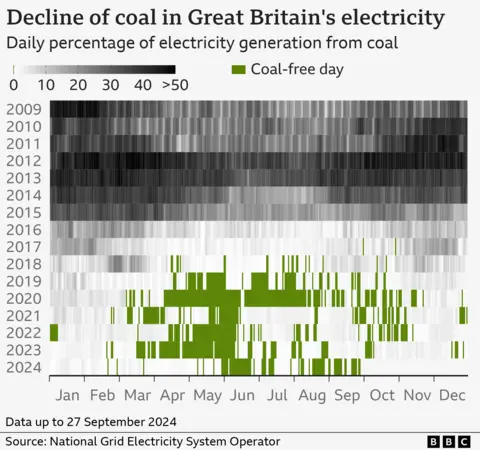

The rapid growth of green power meant that coal could even be switched off completely for short periods, beginning in 2017.

The growth of renewables has been so successful that the target date for ending coal power was brought forward a year, and on Monday, Ratcliffe-on-Soar, was set to close for the last time.

Chris Smith has worked at the plant for 28 years in the environment and chemistry team. She said: “It is a very momentous day. The plant has always been running and we’ve always been doing our best to keep it operating….It is a very sad moment.”

Lord Deben served in former prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s government when many of the UK’s coal mines were closed and thousands of workers lost their jobs. He said lessons had to be learnt from that for current workers in the fossil fuel industry.

“I’m particularly keen on the way in which this Government, and indeed the previous Government, is trying to make sure that the new jobs, of which there are very many green jobs, go to the places which are being damaged by the changes.

“So in the North Sea oil areas, that’s exactly where we should be doing carbon capture and storage, it’s where we should be putting wind and solar power,” he said.

Challenges ahead

Although coal is a very polluting source of energy, its benefit has been in being available at all times – unlike wind and solar which are limited by weather conditions.

Kayte O’Neill, the chief operating officer at the Energy System Operator – the body overseeing the UK’s electricity system – said: “There is a whole load of innovation required to help us ensure the stability of the grid. Keeping the lights on in a secure way.”

A crucial technology providing that stability Kayte O’Neill spoke of is battery technology.

Dr Sylwia Walus, research programme manager at the Faraday Institution, said that there has been significant progress in the science of batteries.

“There is always scope for a new technology, but more focus these days is really how to make it more sustainable and cheaper in production,” she said.

To achieve this the UK needs to become more independent of China in producing its own batteries and bringing in skilled workers for this purpose, she explained.

Additional reporting by Miho Tanaka and Justin Rowlatt