Unemployment may be down, but so are vacancies, while the more timely and reliable payroll data points to a jobs market that looks more like it did in 2019. That period saw wage growth of 3.5%, not the 5% we see today. It’ll take time, but that’s the direction of travel for wages over the coming months and if we’re right, it means faster Bank of England cuts.

Over in the US, the Federal Reserve has made a big call that the jobs market is no longer a source of inflation. And more than that, Chair Jerome Powell has told us he doesn’t welcome any further increase in unemployment.

So far, we’ve not seen that sort of signal here in the UK. The Bank of England still speaks of employment growth that’s more robust than the official figures are telling us. And those latest official numbers show another fall in the unemployment rate, down to 4.0%.

The hawks, meanwhile, are concerned that wage growth will remain a problem for some time to come. Private sector wage growth, though fractionally lower, is still at 4.8% on a year-on-year basis.

Other parts of the jobs report, however, pour cold water on some of that narrative. We know for instance that the unemployment data is of dubious quality, as the Office for National Statistics readily admits, owing to long-running sampling issues. The more timely and in theory more reliable data taken directly from payroll systems, suggests the jobs market has cooled more noticeably so far this year.

Admittedly, that’s not necessarily obvious at the headline level. The number of total payrolled employees did fall fractionally in September, though that will most likely get revised up. But the story is less resilient once government-related sectors are excluded. Taking out things like education, health, and public administration (see chart), this measure of employment is down by 0.8% since the turn of the year. That equates to a fall of 150,000 workers.

Payrolled employment is down when government sectors excluded

Source: Macrobond, ING calculations

Those are not huge numbers, but they do cast some doubt on the BoE’s view that the official data understates jobs growth.

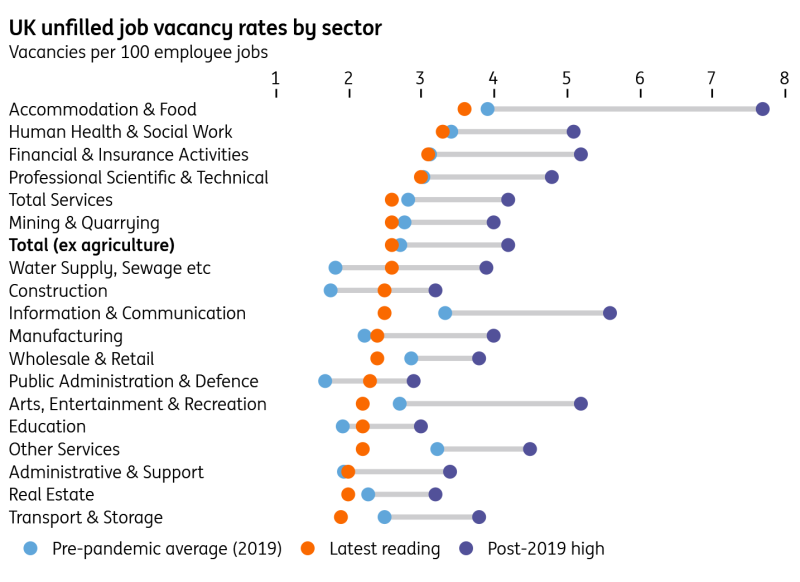

It’s a similar picture with vacancies. Though far from a new development, and with one or two notable exceptions, every sector’s vacancy rate is at or below pre-Covid averages now. Admittedly that 2018/19 period was a pretty strong one for the jobs market by historical standards. Even so, private-sector wage growth during that time was 3.5%, not the circa 5% rates we’re seeing currently.

That is the conundrum the Bank of England now faces. The data is telling us the jobs market is back to pre-Covid normality, and that should mean lower wage growth. All the models will tell you that, too. So why is wage growth still much higher?

Vacancy rates are generally below 2019 averages

Source: Macrobond, ING calculations

One possibility – and one the BoE is thinking bout – is that there’s still some catch-up occurring, as households and businesses battle it out to make up lost income from the recent energy shock. Alternatively, price/wage setting behaviour might have changed in a way that will make it harder to get wage growth and services inflation down to more comfortable levels.

So long as wage growth stays around 5%, these concerns are unlikely to fade. But surveys, be it from the KMPG/REC survey, or the Bank’s own Decision Maker Panel, suggest wage pressures are fading. We know officials put a lot of faith in these numbers, particularly at a time when there’s still scepticism over what the headline employment figures are telling us.

Add in the fact that services inflation is likely to undershoot the BoE’s forecasts over the rest of the year and we think the committee as a whole should become more relaxed. We got a whiff of this in a recent Guardian interview with Governor Andrew Bailey, where he said the Bank could get a “bit more aggressive on cuts”

We expect rate cuts in November and December, and at every subsequent meeting until Bank Rate hits 3.25% next summer.

Read the original analysis: UK jobs market is cooling despite latest fall in unemployment