Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow much is too much for a caffeine fix?

Prices like £5 in London or $7 in New York for a cup of coffee may be unthinkable for some – but could soon be a reality thanks to a “perfect storm” of economic and environmental factors in the world’s top coffee-producing regions.

The cost of unroasted beans traded in global markets is now at a “historically high level”, says analyst Judy Ganes.

Experts blame a mix of troubled crops, market forces, depleted stockpiles – and the world’s smelliest fruit.

So how did we get here, and just how much will it impact your morning latte?

In 2021, a freak frost wiped out coffee crops in Brazil, the world’s largest producer of Arabica beans – those commonly used in barista-made coffee.

This bean shortfall meant buyers turned to countries like Vietnam, the primary producer of Robusta beans, that are typically used in instant blends.

But farmers there faced the region’s worst drought in nearly a decade.

Climate change has been affecting the development of coffee plants, according to Will Frith, a coffee consultant based in Ho Chi Minh City, in turn impacting bean yields.

And then Vietnamese farmers pivoted to a smelly, yellow fruit – the durian.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe fruit – which is banned on public transport in Thailand, Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong because of its odour – is proving popular in China.

And Vietnamese farmers are replacing their coffee crops with durian to cash in on this emerging market.

Vietnam’s durian market share in China almost doubled between 2023 and 2024, and some estimate the crop is five times more lucrative than coffee.

“There’s a history of growers in Vietnam being fickle in response to market price fluctuations, overcommitting, and then flooding the market with quantities of their new crop,” Mr Frith says.

As they flooded China with durian, Robusta coffee exports were down 50% in June compared to the previous June, and stocks were now “near depleted”, according to the International Coffee Organisation.

Exporters in Colombia, Ethiopia, Peru and Uganda have stepped up, but have not produced enough to ease a tight market.

“Right at [the] time when things started to rev up for demand of Robusta, is right when the world was scrambling for more supply,” explains Ms Ganes.

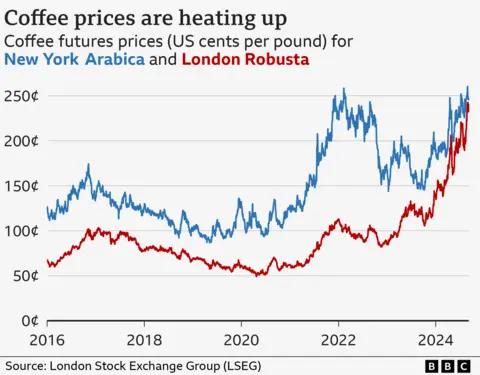

This means Robusta and Arabica beans are now trading at near-record highs on commodity markets.

A brewing market storm

Is the shifting global coffee economy actually impacting the price of your coffee on a high street? The short answer: potentially.

Wholesaler Paul Armstrong believes coffee drinkers may soon face the “crazy” prospect of paying more than £5 in the UK for their caffeine fix.

“It’s a perfect storm at the minute.”

Mr Armstrong, who runs Carrara Coffee Roasters based in the East Midlands, imports beans from South America and Asia, which are then roasted and sent to cafés around the UK.

He tells the BBC he recently increased his prices, hoping it would account for the higher asking prices – but says costs have “only intensified” since.

He adds that with some of his contracts ending in the coming months, cafés he serves will soon have to decide whether to pass the higher costs on to their customers.

Mr Frith says some segments of the industry will be more exposed than others, though.

“It’s really the commercial quantity coffee that will experience the most disuption. Instant coffee, supermarket coffee, stuff at the gas station – that’s all going up.”

Industry figures caution that a high market price for coffee may not necessarily translate into higher retail prices.

Felipe Barretto Croce, CEO of FAFCoffees in Brazil, agrees that consumers are “feeling the pinch” as consumer prices have risen.

But he argues that is “mostly due to inflationary costs in general”, such as rent and labour, rather than the cost of beans. Consultancy Allegra Strategies estimates beans contribute less than 10% of the price of a cup of coffee.

“Coffee is still very cheap, as a luxury good, if you make it at home.”

He also says that the cost of lower-quality beans rising means high-quality coffee may now be seen as better value.

“If you go into a speciality coffee shop in London and get a coffee, versus a coffee in Costa Coffee, the difference [in price] between that cup and the speciality coffee is much smaller than it used to be.”

But there is hope of price relief on the horizon.

Losing future ground

The upcoming spring crop in Brazil, which produces a third of the world’s coffee, is now “crucial”, according to Mr Croce.

“What everyone is looking at is when the rains will return,” he says.

“If they return early, the plants should be healthy enough and the flowering should be good.”

But if the rains come as late as October, he adds, yield predictions for next year’s crop will fall and market stress will continue.

In the long term, climate change poses serious challenges for the global coffee industry.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA study from 2022 concluded that even if we drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the area most highly suited for growing coffee could decline by 50% by 2050.

One measure to future-proof the industry that has the support of Mr Croce is a “green premium” – a small tax levied on coffee given to farmers to invest in regenerative agricultural practices, which help protect and sustain the viability of farmlands.

So while smelly fruit is partly responsible for price rises now – a changing climate may ultimately strain the affordability of coffee in the years to come.